A little note before reading: This is my personal Substack, a space for everything I write that doesn’t quite fit into the structured world of beauty (which I share on my main Substack, soft glow) or my explorations of practical, post-woo-woo wellness (soft realm.) Here, you’ll find all kinds of writing - - zeitgeist observations, messy diary entries, and everything in between. I just started this one and I’m so grateful to you, my first subscribers! <3

This particular piece has been sitting on the shelf since October, but after reading this brilliant 2025 trend report by , where she explores playful surrealism, mass meme-ification, and dystopian chaos, I was thrilled to realise it’s still relevant. So here we go:

Brands are diving headlong into the surreal, embracing chaotic, low-cost ads that seem to thrive on humour and nonsense. There’s something both disarming and alluring about these ads - they feel almost like an inside joke between creator and viewer, unpolished but oddly effective.

Inspired by Jonas Kooyman’s

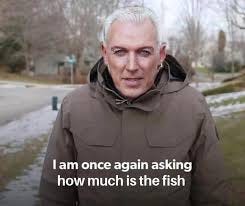

piece on “internet brain rot” (in Dutch) and his dissection of Marc Jacobs’ TikTok ads, I felt compelled to explore what’s going on here. This new brand of advertising plays with our brain’s dopamine, memory, and sense of social connection, creating a tone (or do we rather say.. vibe?) that feels more human, relatable, and lasting than the carefully curated luxury ads of the past.The phenomenon is not exactly new. It has echoes from pop culture’s stranger corners. The 90s pop group The KLF, a duo known as much for their music as for their quirky philosophy on what makes a “hit,” argued that lyrics should be “short, absurd, and easily repeatable.” They practiced what they preached, making their music memorable by embracing repetition and nonsense. This approach paved the way for later artists like Scooter, whose track “How Much Is the Fish?” - with its nonsensical refrain cloaked in chaos - embodied a similar spirit of catchy absurdity. Fast-forward to the early 2000s, and Crazy Frog is an example of taking the concept even further, combining cartoonish sounds with an unpredictable style that commanded attention and defied reason.

Today, brands like Marc Jacobs, Loewe, and even RyanAir are embracing similar principles, leveraging TikTok’s wild-west format to drop the pretence and go straight for the chaotic. Marc Jacobs’ TikTok campaigns (part ad, part absurdist theatre) break down the traditional luxury aesthetic, turning something once untouchable into something (paradoxically) far more relatable. Loewe revels in disjointed visuals that blur the line between advertising and art, while RyanAir caricatures its own customer service complaints.

Together, they create what some might call internet brain rot: a swirl of humour, absurdity, and bite-sized spectacle, all tailor-made for our swipe-happy world.

Absurdism and dopamine: why our brains seek novelty and repetition

Absurdist advertising appeals to our brain’s dopamine pathways. Neuroscience research reveals that short, repetitive sounds and visuals can activate dopamine, the brain’s pleasure chemical, creating a “reward loop” that keeps us engaged. Robert Sapolsky explains that dopamine fuels anticipation as much as it responds to rewards, reinforcing behaviour each time the content is encountered.

TikTok’s sound design taps into this dopamine cycle. The platform’s rapid, catchy sounds create dopamine spikes similar to those seen in gambling, where the randomness of rewards - a funny clip, an unexpected sound - keeps users engaged through a cycle of rapid reward. This phenomenon, sometimes referred to as “TikTok brain,” is rooted in a feedback loop where dopamine is repeatedly triggered by short-form, high-stimulation content.

The KLF recognised this appeal long before social media strategy existed, noting in their manifesto that “nonsense is powerful” because it disrupts expectations. By making their lyrics short, absurd, and repetitive, they found that small doses of chaos could be more memorable than coherence.

Marc Jacobs captures this dynamic in the brands’ TikTok ads, using absurd visuals to reimagine luxury as accessible and humorous.

Memory encoding and meme theory: the stickiness of absurdist content

Absurdist advertising taps into our brain’s memory processes through “chunking” and mnemonic encoding. “Chunking” is the brain’s way of grouping repeatable elements for easier recall, and absurd phrases or visuals like “How Much Is the Fish?” or Marc Jacobs’ ad snippets serve as memorable “chunks” that defy ordinary language but fit our brain’s preference for digestible information.

Marshall McLuhan’s Understanding Media introduced the idea of “hot” versus “cool” media. “Hot” media, like film or radio, provide rich detail, requiring less audience participation, while “cool” media, like television and comics, engage audiences more actively. TikTok moves between these categories but is mainly participatory, inviting remixing and reinterpretation.

TikTok’s meme culture embodies the participatory nature of “cool” media: quick, relatable, and easily remixable. As Limor Shifman writes in Memes in Digital Culture, memes thrive by fostering a shared visual language that encourages familiarity and participation. TikTok’s structure allows users to reinterpret and iterate on trends, creating a dynamic, communal form of engagement.

Ads from brands like Marc Jacobs and Loewe use shared humour to embed themselves into digital culture as memorable chunks rather than overt sales tactics.

Moreover, studies suggest that TikTok’s short videos can create “proactive interference” in memory, where each video disrupts the brain’s processing and consolidation of the last one, limiting the mind's capacity for deeper cognitive processing. This reliance on rapid, instant experiences favours short-term memory but challenges our ability to engage with content more deeply. As Kooyman notes in his recent Havermelkelite newsletter, his own experience with TikTok has led to a vocabulary shaped by snippets of internet culture - phrases like girl dinner, aesthetic and very demure - echoing how the brain absorbs and retains these quick, repetitive patterns. Reflecting on this trend, Kooyman writes, “It feels like my vocabulary has shrunk, as though my attention span itself is being calibrated to the fast, fragmentary rhythm of social media.”

Humour, social bonding, and the rise of the inside joke

Absurdist ads foster more than just memory - they build a sense of community, creating a collective language that is as much social currency as it is entertainment. Giacomo Rizzolatti, known for his work on mirror neurons, found that observing others’ reactions activates empathy centres in the brain, producing what he calls “empathic resonance.” Meme culture amplifies this effect, forming a shared language and giving brands the chance to transcend their corporate identities to become something like “in-group” insiders.

What’s notable is how this phenomenon spills over from the digital world into face-to-face interactions. Inspired by surreal digital content, I’ve noticed that people in my own and others' friend groups or social settings are slipping into absurd phrases or gestures that seem plucked straight from a meme - or sometimes literally are. It’s as if the act of sharing a meme has become something more: a shared, real-world language built around inside jokes, echoing John Fiske’s concept of “bricolage,” where cultural fragments are pieced together to create something new and meaningful.

The Oddball Effect and the power of absurdity

Absurdist content captures our attention in part through the “oddball effect,” a cognitive response where our brains light up in reaction to unexpected stimuli. Neuroscientist Michael W. Beck explains that odd, bizarre visuals create “attention spikes” as our brains work to make sense of them. Loewe’s TikTok ads, which are packed with disjointed colours, sounds, and visuals, exemplify this concept - they captivate by delivering the unexpected, creating a cognitive dissonance that anchors them in memory.

The KLF’s statement that 'nonsense is powerful because it grabs attention' perfectly encapsulates this effect.

Absurdist advertising and the limits of relatability

While effective, this rise of meme-inspired advertising raises questions about long-term brand building. In chasing relatability, brands risk trapping themselves in a cycle of cultural mimicry, reducing complex ideas to easily digestible aesthetics. Authentic brand-building requires depth, storytelling, and coherence, qualities that don’t always align with TikTok’s dopamine-driven playbook.

Yet, there’s an undeniable appeal to this new unseriousness. Absurd, low-cost ads are pushing us toward a lighter, more playful self-expression that transcends the screen, blending into real life. In a world obsessed with productivity and polish, there’s something refreshing - if not downright necessary - about being “unserious.”

But it also makes me think of the political contexts of absurdist art movements like Dada and Fluxus. Dada emerged in Zurich in 1916, during the devastation of World War I, which left Europe in political and moral disarray. The movement was a reaction to the irrationality of war, nationalism, and the failures of traditional institutions. Dada artists rejected logic, reason, and aesthetic norms, seeing them as complicit in the systems that led to war. They embraced nonsense, chance, and anti-art as a way to challenge the status quo. Fluxus emerged in the early 1960s, during the height of the Cold War, the rise of mass consumer culture, and global political unrest (Vietnam War, Civil Rights Movement, student protests).

In our current times of political unrest and creeping dystopia, it’s no surprise that absurdism and surrealism are making a comeback. And rather than emerging through art, they find their strongest foothold in advertising - an industry deeply entwined with late-stage capitalism, the very system shaping our current reality.

Psychology

Research in psychology shows that humour, even surreal humour, plays a key role in social bonding and well-being, allowing us to connect over shared absurdities in ways that feel honest and personal.

Absurdity in branding might not save the world, but it reminds us that a bit of collective silliness is anything but trivial - it’s connection. The KLF may have seen absurdity as a means to an end, but today’s brands (unintentionally?) reveal it as an end in itself: a space where humour and humanity intersect, allowing us to be unserious together, navigating our current reality.

Sources

1. Sapolsky, Robert M. Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst. Penguin, 2017.

2. "Same Neurochemistry, One Difference: Dr. Robert Sapolsky on Dopamine." The Dopamine Project, 2011.

3. Baddeley, Alan D. Human Memory: Theory and Practice. Psychology Press, 1997.

4. Miller, George A. "The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information." Psychological Review, vol. 63, no. 2, 1956, pp. 81-97.

5. McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. McGraw-Hill, 1964.

6. Drummond, Bill, and Jimmy Cauty. The Manual (How to Have a Number One the Easy Way). The KLF, 1988.

7. Neuroscience of TikTok Addiction. ReNu Counselling.

8. TikTok is Killing Your Brain, One Short-Form Video at a Time Social Media Psychology, Aug 2022.

9. Shifman, Limor. Memes in Digital Culture. MIT Press, 2013.

10. Fiske, John. Understanding Popular Culture. Routledge, 1989.